Advanced JavaScript Cheat Sheet 💻🚀

We created this JavaScript Cheat Sheet for students of our JavaScript: The Advanced Concepts to help them as they learn modern, advanced JavaScript practices and become top 10% JavaScript developers.

But we've now made it available for free to help any and all web developers learn and remember common JavaScript concepts.

Warning: this cheat sheet is a beast. We highly recommend that you bookmark this page or download the PDF.

Want to download a PDF version of this Advanced JavaScript Cheat Sheet?

Enter your email below and we'll send it to you 👇

Unsubscribe anytime.

If you’ve stumbled across this page and are just starting to learn JavaScript, congrats! Being a web developer is a fantastic career option and industry demand for JavaScript developers is HUGE.

If you're new to JavaScript, check out our free step-by-step guide that will teach you how to learn how to code (HTML, CSS, JS, React + more) & get hired in 5 months (and even have fun along the way).

If you're already a web developer but stuck in a junior or intermediate role, let us help fast track you to get the knowledge that Senior Javascript Developers have in just 30 days.

By the end of our Advanced JavaScript Concepts course, you will be in the top 10% of JavaScript Programmers.

Enough jibber-jabber from us, please enjoy this guide and if you'd like to submit any corrections or suggestions, please feel free to email us at support@zerotomastery.io

Contents

JavaScript Engine

Writing Optimized Code

Call Stack and Memory Heap

Stack Overflow

- Garbage Collection

- Synchronous

- Event Loop and Callback Queue

- Job Queue

- 3 Ways to Promise

- Threads, Concurrency, and Parallelism

Execution Context

Hoisting

Lexical Environment

Scope Chain

Function and Block Scope

IIFE - Immediately Invoked Function Expression

This

Call, Apply, Bind

JavaScript Types

The 2 Pillars: Closures and Prototypes

- Function Constructor

- Prototypal Inheritance

- Prototype vs proto

- Callable Object

- Higher Order Functions

- Closures

- Memory Efficient

- Encapsulation

Object Oriented Programming

- Object Oriented Programming

- Factory Functions

- Stores

- Object.create

- Constructor Functions

- Class

- Private and public fields

Functional Programming

- Pure Functions

- Referential transparency

- Idempotence

- Imperative vs Declarative

- Immutability

- Partial Application

- Pipe and Compose

- Arity

Composition vs Inheritance

Modules in JavaScript

Error Handling

The End...

Data Structures & Algorithms

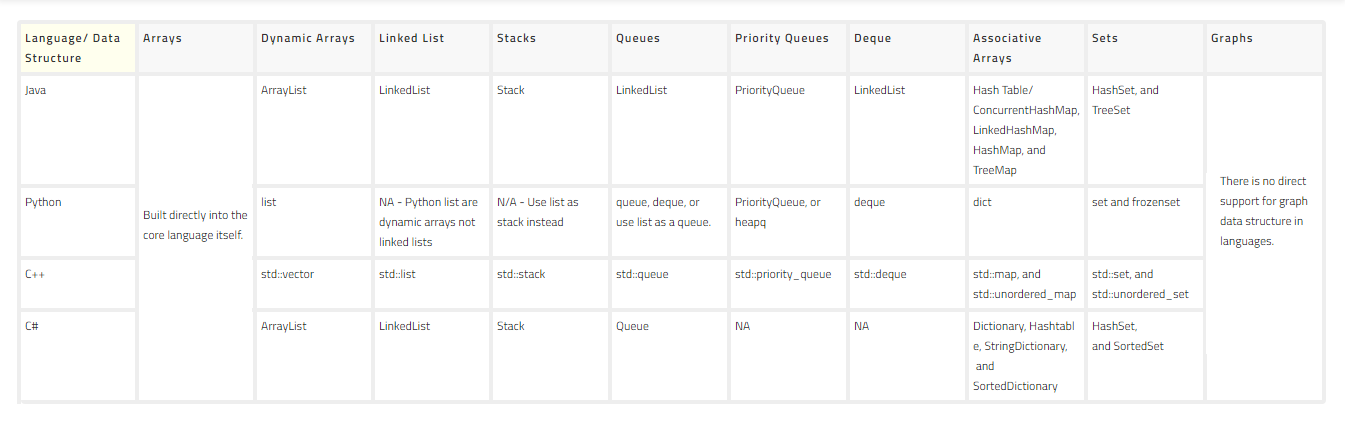

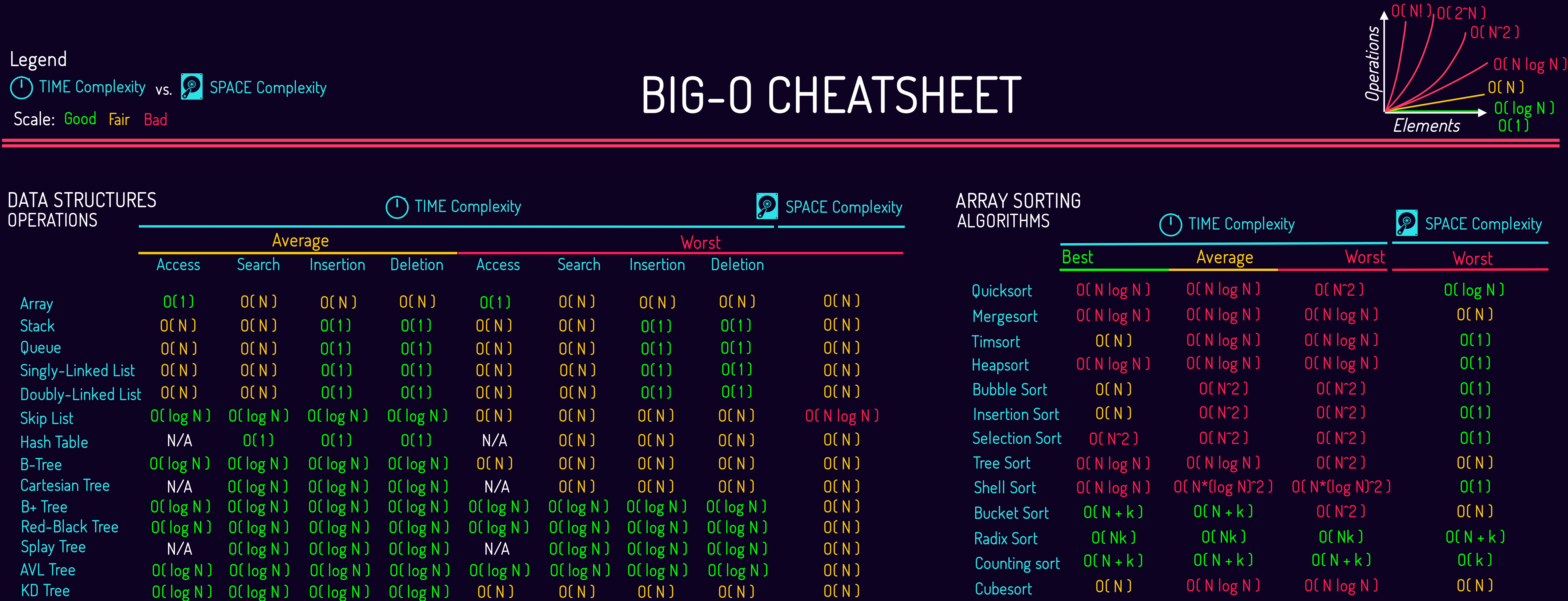

- Data Structures

- How do computers work?

- Popular Data Structures

- Arrays

- Implementing an Array

- Hash tables

- Hash Collisions

- Hashing in JavaScript

- Create a Hash Table

Credits

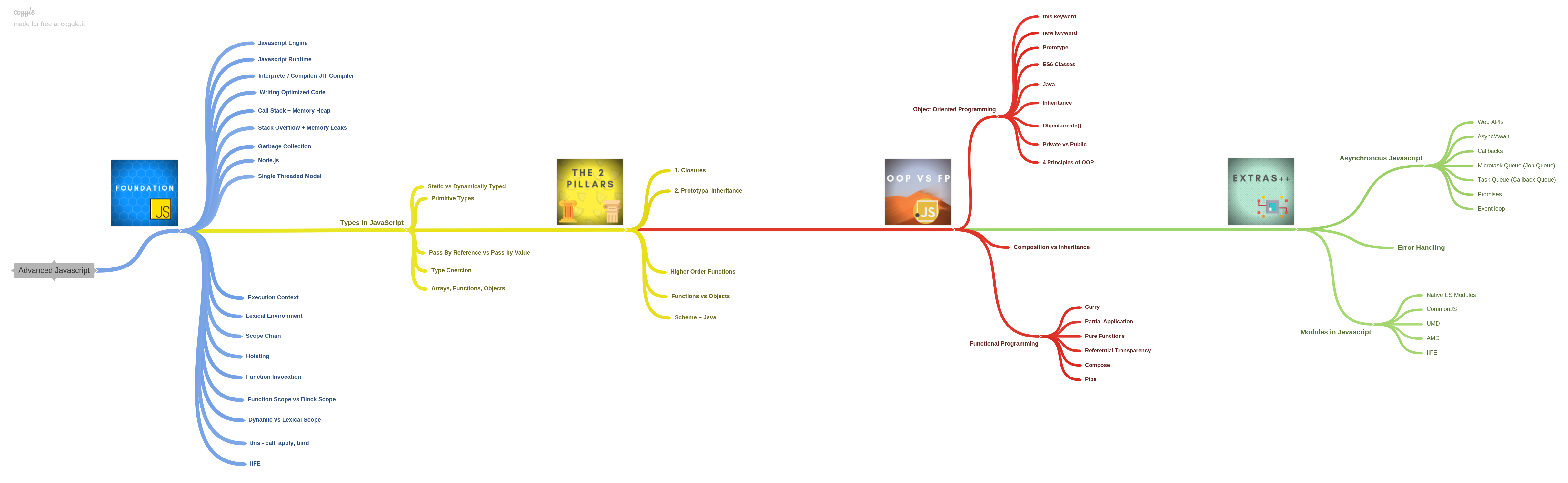

Course Map

JavaScript Engine

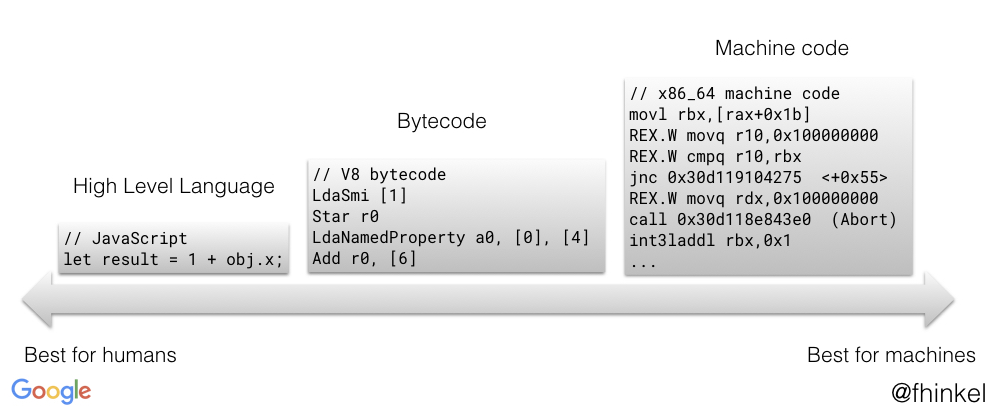

A JavaScript engine is a computer program that you give JavaScript code to and it tells the computer how to execute it. Basically a translator for the computer between JavaScript and a language that the computer understands.

But what happens inside of the engine? Well, that depends on the engine.

There are many JavaScript Engines out there and typically they are created by web browser vendors. All engines are standardized by ECMA Script or ES.

Nifty Snippet: 2008 was a pivotal moment for JavaScript when Google created the Chrome V8 Engine.

The V8 engine is an open source high-performance JavaScript engine, written in C++ and used in the Chrome browser and powers Node JS.

The performance outmatched any engine that came before it mainly because it combines 2 parts of the engine, the interpreter and the compiler. Today, all major engines use this same technique.

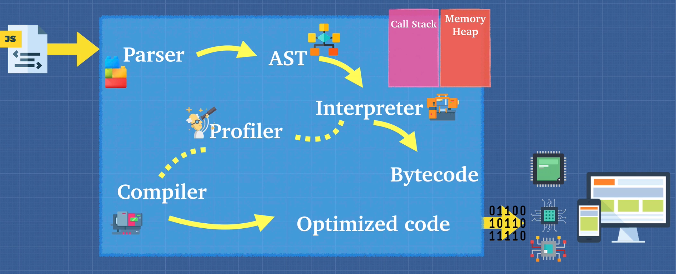

The Parser

Parsing is the process of analyzing the source code, checking it for errors, and breaking it up into parts.

The AST

The parser produces a data structure called the Abstract Syntax Tree or AST.

AST is a tree graph of the source code that does not show every detail of the original syntax, but contains structural or content-related details. Certain things are implicit in the tree and do not need to be shown, hence the title abstract.

The Interpreter

An interpreter directly executes each line of code line by line, without requiring them to be compiled into a machine language program.

Interpreters can use different strategies to increase performance. They can parse the source code and execute it immediately, translate it into more efficient machine code, execute precompiled code made by a compiler, or some combination of these.

In the V8 engine, the interpreter outputs bytecode.

Nifty Snippet: The first JavaScript engine was written by Brendan Eich, the creator of JavaScript, in 1995 for the Netscape navigator web browser. Originally, the JavaScript engine only consisted of an interpreter. This later evolved into the SpiderMonkey engine, still used by the Firefox browser.

The Compiler

The compiler works ahead of time to convert instructions into a machine-code or lower-level form so that they can be read and executed by a computer. It runs all of the code and tries to figure out what the code does and then compiles it down into another language that is easier for the computer to read.

Have you heard of Babel or TypeScript?

They are heavily used in the Javascript ecosystem and you should now have a good idea of what they are.

Babel is a Javascript compiler that takes your modern JS code and returns browser compatible JS (older JS code).

Typescript is a superset of Javascript that compiles down to Javascript. Both of these do exactly what compilers do. Take one language and convert into a different one!

The Combo

In modern engines, the interpreter starts reading the code line by line while the profiler watches for frequently used code and flags then passes is to the compiler to be optimized.

In the end, the JavaScript engine takes the bytecode the interpreter outputs and mixes in the optimized code the compiler outputs and then gives that to the computer. This is called "Just in Time" or JIT Compiler.

Nifty Snippet: Back in 1995 we had no standard between the browsers for compiling JavaScript. Compiling code on the browser or even ahead of time was not feasible because all the browsers were competing against each other and could not agree on an executable format.

Even now, different browsers have different approaches on doing things. Enter WebAssembly a standard for binary instruction (executible) format. Keep your eye on WebAssembly to help standardize browsers abilities to exectute JavaScript in the future!

Writing Optimized Code

We want to write code that helps the compiler make its optimizations, not work against it making the engine slower.

Memoization

Memoization is a way to cache a return value of a function based on its parameters. This makes the function that takes a long time run much faster after one execution. If the parameter changes, it will still have to reevaluate the function.

// Bad Way

function addTo80(n) {

console.log('long time...')

return n + 80

}

addTo80(5)

addTo80(5)

addTo80(5)

// long time... 85

// long time... 85

// long time... 85

// Memoized Way

functions memoizedAddTo80() {

let cache = {}

return function(n) { // closure to access cache obj

if (n in cache) {

return cache[n]

} else {

console.log('long time...')

cache[n] = n + 80

return cache[n]

}

}

}

const memoized = memoizedAddTo80()

console.log('1.', memoized(5))

console.log('2.', memoized(5))

console.log('3.', memoized(5))

console.log('4.', memoized(10))

// long time...

// 1. 85

// 2. 85

// 3. 85

// long time...

// 4. 90Here are a few things you should avoid when writing your code if possible:

- eval()

- arguments

- for in

- with

- delete

There are a few main reasons these should be avoided.

Inline Caching

function findUser(user) {

return `found ${user.firstName} ${user.lastName}`

}

const userData = {

firstName: 'Brittney',

lastName: 'Postma

}

findUser(userData)

// if this findUser(userData) is called multiple times,

// then it will be optimized (inline cached) to just be 'found Brittney Postma'If this code gets optimized to return only 1 name, then the computer would have to do a lot more work if you needed to return a different user.

Hidden Classes

function Animal(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

const obj1 = new Animal(1, 2);

const obj2 = new Animal(3, 4);

obj1.a = 30;

obj1.b = 100;

obj2.b = 30;

obj2.a = 100;

delete obj1.x = 30;By setting these values in a different order than they were instantiated, we are making the compiler slower because of hidden classes.

Hidden classes are what the compiler uses under the hood to say that these 2 objects have the same properties.

If values are introduced in a different order than it was set up in, the compiler can get confused and think they don't have a shared hidden class, they are 2 different things, and will slow down the computation.

Also, the reason the delete keyword shouldn't be used is because it would change the hidden class.

// This is the more optimized version of the code.

function Animal(x, y) {

// instantiating a and b in the constructor

this.a = x;

this.b = y;

}

const obj1 = new Animal(1, 2);

const obj2 = new Animal(3, 4);

// and setting the values in order

obj1.a = 30;

obj1.b = 100;

obj2.a = 30;

obj2.b = 100;Managing Arguments

There are many ways using arguments that can cause a function to be unoptimizable. Be very careful when using arguments and remember:

Safe Ways to Use Arguments

- arguments.length

- arguments[i] when i is a valid integer

- NEVER use arguments directly without .length or [i]

- STRICTLY fn.apply(y, arguments) is ok

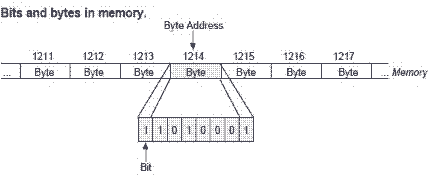

Call Stack and Memory Heap

The JavaScript engine does a lot of work for us, but 2 of the biggest jobs are reading and executing it. We need a place to store and write our data and a place to keep track line by line of what's executing.

That's where the call stack and the memory heap come in.

Memory Heap

The memory heap is a place to store and write information so that we can use our memory appropriately. It is a place to allocate, use, and remove memory as needed. Think of it as a storage room of boxes that are unordered.

// tell the memory heap to allocate memory for a number

const number = 11;

// allocate memory for a string

const string = "some text";

// allocate memory for an object and it's values

const person = {

first: "Brittney",

last: "Postma"

};

Call Stack

The call stack keeps track of where we are in the code, so we can run the program in order.function subtractTwo(num) {

return num - 2;

}

function calculate() {

const sumTotal = 4 + 5;

return subtractTwo(sumTotal);

}

debugger;

calculate();Things are placed into the call stack on top and removed as they are finished. It runs in a first in last out mode. Each call stack can point to a location inside the memory heap. In the above snippet the call stack looks like this.

anonymous; // file is being ran

// CALL STACK

// hits debugger and stops the file

// step through each line

calculate(

// steps through calculate() sumTotal = 9

anonymous

);

// CALL STACK

// steps into subtractTwo(sumTotal) num = 9

subtractTwo; // returns 9 - 2

calculate(anonymous);

// CALL STACK

// subtractTwo() has finished and has been removed

calculate(

// returns 7

anonymous

)(

// CALL STACK

// calculate() has finished and has been removed

anonymous

);

// CALL STACK

// and finally the file is finished and is removed

// CALL STACKStack Overflow

So what happens if you keep calling functions that are nested inside each other? When this happens it's called a **stack overflow**.// When a function calls itself,

// it is called RECURSION

function inception() {

inception();

}

inception();

// returns Uncaught RangeError:

// Maximum call stack size exceededNifty Snippet: Did you know, Google has hard-coded recursion into their program to throw your brain for a loop when searching recursion?

Garbage Collection

JavaScript is a garbage collected language. If you allocate memory inside of a function, JavaScript will automatically remove it from the memory heap when the function is done being called.However, that does not mean you can forget about memory leaks. No system is perfect, so it is important to always remember memory management.

JavaScript completes garbage collection with a mark and sweep method.

var person = {

first: "Brittney",

last: "Postma"

};

person = "Brittney Postma";In the example above a memory leak is created. By changing the variable person from an object to a string, it leaves the values of first and last in the memory heap and does not remove it.

This can be avoided by trying to keep variables out of the global namespace, only instantiate variables inside of functions when possible.

JavaScript is a single threaded language, meaning only one thing can be executed at a time. It only has one call stack and therefore it is a synchronous language.

Synchronous

So, what is the issue with being a single threaded language?

Lets's start from the beginning. When you visit a web page, you run a browser to do so (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Edge). Each browser has its own version of JavaScript Runtime with a set of Web API's, methods that developers can access from the window object.

In a synchronous language, only one thing can be done at a time. Imagine an alert on the page, blocking the user from accessing any part of the page until the OK button is clicked. If everything in JavaScript that took a significant amount of time, blocked the browser, then we would have a pretty bad user experience.

This is where concurrency and the event loop come in.

Event Loop and Callback Queue

When you run some JavaScript code in a browser, the engine starts to parse the code. Each line is executed and popped on and off the call stack.

But, what about Web API's?

Web API's are not something JavaScript recognizes, so the parser knows to pass it off to the browser for it to handle. When the browser has finished running its method, it puts what is needed to be ran by JavaScript into the callback queue.

The callback queue cannot be ran until the call stack is completely empty. So, the event loop is constantly checking the call stack to see if it is empty so that it can add anything in the callback queue back into the call stack. And finally, once it is back in the call stack, it is ran and then popped off the stack.

console.log("1");

// goes on call stack and runs 1

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("2"), 1000;

});

// gets sent to web api

// web api waits 1 sec, runs and sends to callback queue

// the javascript engine keeps going

console.log("3");

// goes on call stack and runs 3

// event loop keeps checking and see call stack is empty

// event loop sends calback queue into call stack

// 2 is now ran

// 1

// 3

// 2

// Example with 0 second timeout

console.log("1");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("2"), 0;

});

console.log("3");

// 1

// 3

// 2

// Still has the same outputIn the last example, we get the same output. How does this work if it waits 0 seconds?

The JavaScript engine will still send off the setTimeout() to the Web API to be ran and it will then go into the callback queue and wait until the call stack is empty to be ran. So, we end up with the exact same end point.

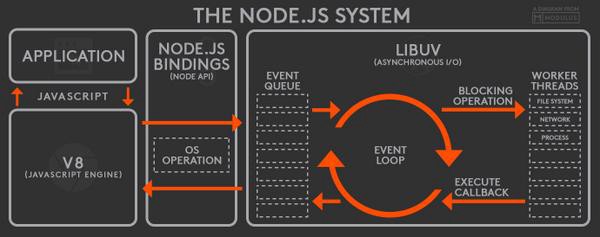

Nifty Snippet: Until 2009, JavaScript was only run inside of the browser. That is when Ryan Dahl decided it would be great if we could use JavaScript to build things outside the browser.

He used C and C++ to build an executable (exe) program called Node JS. Node JS is a JavaScript runtime environment built on Chrome's V8 engine that uses C++ to provide the event loop and callback queue needed to run asynchronous operations.

The very same Ryan Dahl then gave a talk back in 2018, 10 Things I Regret About Node.js which led to the recent release of his new (and improved) JavaScript and TypeScript called Deno which aims to provide a productive and secure scripting environment for the modern programmer. It is built on top of V8, Rust, and TypeScript.

If you're interested in learning Deno, Zero To Mastery instructors, Andrei Neagoie and Adam Odziemkowski (also an official Deno contributor), released the very first comprehensive Deno course.

Job Queue

The job queue or microtask queue came about with promises in ES6. With promises we needed another callback queue that would give higher priority to promise calls. The JavaScript engine is going to check the job queue before the callback queue.

// 1 Callback Queue ~ Task Queue

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("1", "is the loneliest number");

}, 0);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("2", "can be as bad as one");

}, 10);

// 2 Job Queue ~ Microtask Queue

Promise.resolve("hi").then(data => console.log("2", data));

// 3

console.log("3", "is a crowd");

// 3 is a crowd

// 2 hi

// undefined Promise resolved

// 1 is the loneliest number

// 2 can be as bad as one3 Ways to Promise

There are 3 ways you could want promises to resolve, parallel (all together), sequential (1 after another), or a race (doesn't matter who wins).

const promisify = (item, delay) =>

new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(() => resolve(item), delay));

const a = () => promisify("a", 100);

const b = () => promisify("b", 5000);

const c = () => promisify("c", 3000);

async function parallel() {

const promises = [a(), b(), c()];

const [output1, output2, output3] = await Promise.all(promises);

return `parallel is done: ${output1} ${output2} ${output3}`;

}

async function sequence() {

const output1 = await a();

const output2 = await b();

const output3 = await c();

return `sequence is done: ${output1} ${output2} ${output3}`;

}

async function race() {

const promises = [a(), b(), c()];

const output1 = await Promise.race(promises);

return `race is done: ${output1}`;

}

sequence().then(console.log);

parallel().then(console.log);

race().then(console.log);

// race is done: a

// parallel is done: a b c

// sequence is done: a b cThreads, Concurrency, and Parallelism

Even though JavaScript is a single threaded language, there are worker threads that work in the background that don't block the main thread.

Just like a browser creates a new thread when you open a new tab. The workers work through messages being sent, but don't have access to the full program.

var worker = new Worker("worker.js");

worker.postMessage("Helloooo");

addEventListener("message");Execution Context

Code in JavaScript is always run inside a type of execution context. Execution context is simply the environment within which your code is ran.

There are 2 types of execution context in JavaScript, global or function.

There are 2 stages as well to each context, the creation and executing phase.

As the JavaScript engine starts to read your code, it creates something called the Global Execution Context.

Global Execution Context

Creation Phase

- global object created

- initializes this keyword to global

Executing Phase 3. Variable Environment created - memory space for var variables and functions created 4. initializes all variables to undefined (also known as hoisting) and places them with any functions into memory

this;

window;

this === window;

// Window {...}

// Window {...}

// trueFunction Execution Context

Only when a function is invoked, does a function execution context get created.

Creation Phase

- argument object created with any arguments

- initializes this keyword to point called or to the global object if not specified

Executing Phase

- Variable Environment created - memory space for variable and functions created

- initializes all variables to undefined and places them into memory with any new functions

// Function Execution Context creates arguments object and points 'this' to the function

function showArgs(arg1, arg2) {

console.log("arguments: ", arguments);

return `argument 1 is: ${arg1} and argument 2 is: ${arg2}`;

}

showArgs("hello", "world");

// arguments: { 0: 'hello', 1: 'world' }

// argument 1 is hello and argument 2 is world

function noArgs() {

console.log("arguments: ", arguments);

}

noArgs();

// arguments: {}

// even though there are no arguments, the object is still createdThe keyword arguments can be dangerous to use in your code as is. In ES6, a few methods were introduced that can help better use arguments.

function showArgs(arg1, arg2) {

console.log("arguments: ", arguments);

console.log(Array.from(arguments));

}

showArgs("hello", "world");

// arguments: { 0: 'hello', 1: 'world' }

// [ 'hello', 'world' ]

function showArgs2(...args) {

console.log(console.log("arguments: ", args));

console.log(Array.from(arguments));

return `${args[0]} ${args[1]}`;

}

showArgs2("hello", "world");

// arguments: [ 'hello', 'world' ]

// [ 'hello', 'world' ]

// hello worldArrow Functions

Some people think of arrow functions as just being syntactic sugar for a regular function, but arrow functions work a bit differently than a regular function.

They are a compact alternative to a regular function, but also without its own bindings to this, arguments, super, or new.target keywords. Arrow functions cannot be used as constructors and are not the best option for methods.

var obj = { // does not create a new scope i: 10, b: () => console.log(this.i, this), c: function() { console.log(this.i, this); } }; obj.b(); // prints undefined, Window {...} (or the global object) obj.c(); // prints 10, Object {...}```

Hoisting

Hoisting is the process of putting all variable and function declarations into memory during the compile phase.

In JavaScript, functions are fully hoisted, var variables are hoisted and initialized to undefined, and let and const variables are hoisted but not initialized a value.

Var variables are given a memory allocation and initialized a value of undefined until they are set to a value in line. So if a var variable is used in the code before it is initialized, then it will return undefined.

However, a function can be called from anywhere in the code base because it is fully hoisted. If let and const are used before they are declared, then they will throw a reference error because they have not yet been initialized.

// function expression gets hoisted as undefined

var sing = function() {

console.log("uhhhh la la la");

};

// function declaration gets fully hoisted

function sing2() {

console.log("ohhhh la la la");

}// function declaration gets hoisted

function a() {

console.log("hi");

}

// function declaration get rewritten in memory

function a() {

console.log("bye");

}

console.log(a());

// bye// variable declaration gets hoisted as undefined

var favoriteFood = "grapes";

// function expression gets hoisted as undefined

var foodThoughts = function() {

// new execution context created favoriteFood = undefined

console.log(`Original favorite food: ${favoriteFood}`);

// variable declaration gets hoisted as undefined

var favoriteFood = "sushi";

console.log(`New favorite food: ${favoriteFood}`);

};

foodThoughts();Takeaway

Avoid hoisting when possible. It can cause memory leaks and hard to catch bugs in your code. Use let and const as your go to variables.

Lexical Environment

A lexical environment is basically the scope or environment the engine is currently reading code in.

A new lexical environment is created when curly brackets {} are used, even nested brackets {{...}} create a new lexical environment.

The execution context tells the engine which lexical environment it is currently working in and the lexical scope determines the available variables.

function one() {

var isValid = true; // local env

two(); // new execution context

}

function two() {

var isValid; // undefined

}

var isValid = false; // global

one();

/*

two() isValid = undefined

one() isValid = true

global() isValid = false

------------------------

call stack

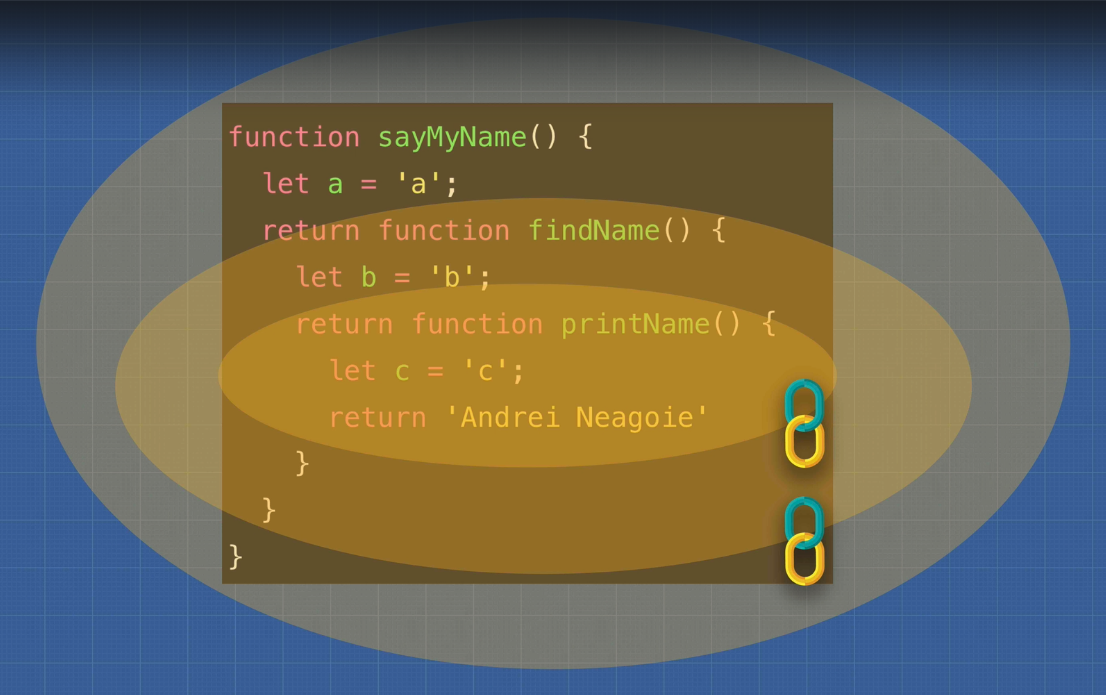

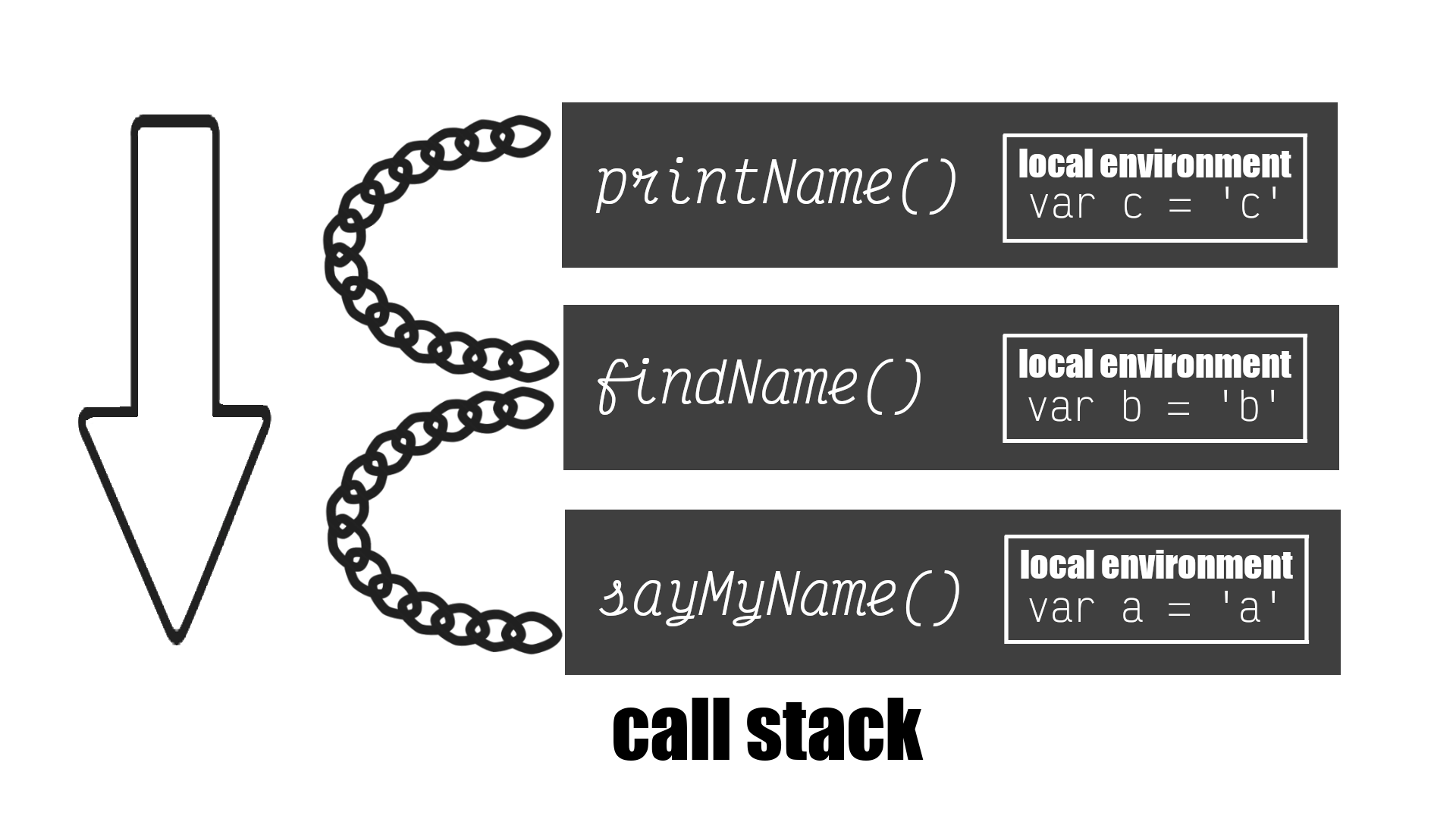

*/Scope Chain

Each environment context that is created has a link outside of its lexical environment called the scope chain. The scope chain gives us access to variables in the parent environment.

var x = "x";

function findName() {

console.log(x);

var b = "b";

return printName();

}

function printName() {

var c = "c";

return "Brittney Postma";

}

function sayMyName() {

var a = "a";

return findName();

}

sayMyName();

// sayMyName runs a = 'a'

// findName runs

// x

// b = 'b'

// printName runs c = 'c'

// Brittney PostmaIn this example, all the functions have access to the global variable x, but trying to access a variable from another function would return an error. The example below will show how the scope chain links each function.

function sayMyName() {

var a = "a";

console.log(b, c); // returns error

return function findName() {

var b = "b";

console.log(a); // a

console.log(c); // returns error

return function printName() {

var c = "c";

console.log(a, b); // a, b

};

};

}

sayMyName()()(); //each function is returned and has to be calledIn this example, you can see that the functions only get access to the variables in their parent container, not a child. The scope chain only links down the call stack, so you almost have to think of it in reverse. It goes up to the parent, but down the call stack.

JavaScript is Weird

// It asks global scope for height.

// Global scope says: ummm... no but here I just created it for you.

// We call this leakage of global variables.

// Adding 'use strict' to the file prevents this and causes an error.

function weird() {

height = 50;

}

var heyhey = function doodle() {

// code here

};

heyhey();

doodle(); // Error! because it is enclosed in its own scope.Function and Block Scope

Most programming languages are block scoped, meaning every time you see a new { } (curly braces) is a new lexical environment.

However, JavaScript is function scoped, meaning it only creates a new local environment if it sees the keyword function on the global scope.

To give us access to block scope, in ES6 let and const were added to the language. Using these can prevent memory leaks, but there is still an argument to be made for using var.

//Function Scope

function loop() {

for (var i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

console.log(i);

}

console.log("final", i); // returns final 5

}

//Block Scope

function loop2() {

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

// can access i here

}

console.log("final", i); // returns an error here

}

loop();

/*

1

2

3

4

final 5

*/

loop2();

// ReferenceError: i is not definedlet and const

Variable declarations with let and const work differently from the var variable declaration and I wanted to take a minute to explain.

When a lexical scope is entered and the execution context is created, the engine allocates memory for any var variable in that scope and initializes it to undefined.

The let and const variables only get initialized on the line they are executed on and only get allocated undefined if there is no assignment to the variable. Trying to access a let or const variable before it is declared or outside of its block without returning it will result in a Reference Error.

IIFE - Immediately Invoked Function Expression

Immediately Invoked Function Expression or more simply IIFE is a JavaScript function that runs as soon as it is defined. Can also be referred to as a Self-Executing Anonymous Function.

// Grouping Operator () creates a lexical scope

(function() {

// statements

})();

// Immediately invokes the function with 2nd set of ()Takeaway: Avoid polluting the global namespace or scope when possible.

this

Here we are... The moment has arrived, time to talk about this.

What is this?

Why is this so confusing?

For some, this is the scariest part of JavaScript. Well, hopefully we can clear some things up.

this is the object that the function is a property of

There that's simple right? Well, maybe not, what does that mean?

Back in Execution Context, we talked about how the JavaScript engine creates the global execution context and initializes this to the global window object.

this; // Window {...}

window; // Window {...}

this === window; // true

function a() {

console.log(this);

}

a();

// Window {...}In the example above, it is easy to understand that this is equal to the window object, but what about inside of function a?

Well, what object is function a apart of?

In the dev tools, if you expand the window object and scroll down the list, you will see a() is a method on the window object. By calling a(), you are essentially saying window.a() to the console.

const obj = {

property: `I'm a property of obj.`,

method: function() {

// this refers to the object obj

console.log(this.property);

}

};

obj.method();

// I'm a property of obj.this refers to whatever is on the left of the . (dot) when calling a method

// obj is to the left of the dot

obj.method();Still confused? Try this:

function whichName() {

console.log(this.name);

}

var name = "window";

const obj1 = {

name: "Obj 1",

whichName

};

const obj2 = {

name: "Obj 2",

whichName

};

whichName(); // window

obj1.whichName(); // Obj 1

obj2.whichName(); // Obj 2Another way to look at this is to check which object called it.

const a = function() {

console.log("a", this);

const b = function() {

console.log("b", this);

const c = {

hi: function() {

console.log("c", this);

}

};

c.hi(); // new obj c called function

};

b(); // ran by a window.a(b())

};

a(); // called by window

// a Window {…}

// b Window {…}

// c {hi: ƒ}Here is this 4 ways:

-

new keyword binding - the new keyword changes the meaning of this to be the object that is being created.

-

implicit binding - "this" refers to the object that is calling it. It is implied, without doing anything its just how the language works.

-

explicit binding - using the "bind" keyword to change the meaning of "this".

-

arrow functions as methods - "this" is lexically scoped, refers to it's current surroundings and no further. However, if "this" is inside of a method's function, it falls out of scope and belongs to the window object. To correct this, you can use a higher order function to return an arrow function that calls "this".

// new binding

function Person(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

console.log(this);

}

const person1 = new Person("person1", 55);

// this = Person { name: 'person1', age: 55 }

//implicit binding

const person = {

name: "person",

age: 20,

hi() {

console.log("hi " + this);

}

};

person.hi();

// this = person { name: 'person', age: 20, hi(){...} }

//explicit binding

let name = "Brittney";

const person3 = {

name: "person3",

age: 50,

hi: function() {

console.log("hi " + this.name);

}.bind(window)

};

person3.hi();

// hi Brittney

// this = window {...}

// arrow functions inside objects

const person4 = {

name: "person4",

age: 40,

hi: function() {

var inner = () => {

console.log(this);

};

return inner();

}

};

person4.hi();

// this = person4 { name: 'person4', age: 40, hi() {...} }

// if either function is changed around, it doesn't workLexical vs Dynamic Scope

A big gotcha for a lot of people working with *this is when a function is ran inside of another function. It gets a little confusing, but we can remember who called the function.

const obj = {

name: "Billy",

sing() {

console.log("a", this);

var anotherFunc = function() {

console.log("b", this);

};

anotherFunc();

}

};

obj.sing();

// a {name: "Billy", sing: ƒ}

// b Window {…}In the example above, the obj called sing() and then anotherFunc() was called within the sing() function.

In JavaScript, that function defaults to the Window object. It happens because everything in JavaScript is lexically scoped except for the this keyword.

It doesn't matter where it is written, it matters how it is called.

Changing anotherFunc() instead to an arrow function will fix this problem, as seen below. Arrow functions do not bind or set their own context for this.

If this is used in an arrow function, it is taken from the outside. Arrow functions also have no arguments created as functions do.

const obj = {

name: "Billy",

sing() {

console.log("a", this);

var anotherFunc = () => {

console.log("b", this);

};

anotherFunc();

}

};

obj.sing();

// a {name: "Billy", sing: ƒ}

// b {name: "Billy", sing: ƒ}Okay, last example to really solidify our knowledge of this.

var b = {

name: "jay",

say() {

console.log(this);

}

};

var c = {

name: "jay",

say() {

return function() {

console.log(this);

};

}

};

var d = {

name: "jay",

say() {

return () => console.log(this);

}

};

b.say(); // b {name: 'jay', say()...}

// b called the function

c.say(); // function() {console.log(this)}

// returned a function that gets called later

c.say()(); // Window {...}

// c.say() gets the function and the Window runs it

d.say(); // () => console.log(this)

// returned the arrow function

d.say()(); // d {name: 'jay', say()...}

// arrow function does not rebind this and inherits this from parentAfter everything is said and done, using this can still be a bit confusing. If you aren't sure what it's referencing, just console.log(this) and see where it's pointing.

Nifty Snippet: Context and Scope can sometimes be confusing terms in JavaScript.

Context refers to the value of the this keyword.

Scope refers to the current context and visibility of variables.

Call, Apply, Bind

Call

Call is a method of an object that can substitute a different object than the one it is written on.

const wizard = {

name: "Merlin",

health: 100,

heal(num1, num2) {

return (this.health += num1 + num2);

}

};

const archer = {

name: "Robin Hood",

health: 30

};

console.log(archer); // health: 30

wizard.heal.call(archer, 50, 20);

console.log(archer); // health: 100In this example call is used to borrow the heal method from the wizard and is used on the archer (which is actually pointing this to archer), with the optional arguments added.

Apply

Apply is almost identical to call, except that instead of a comma separated list of arguments, it takes an array of arguments.

// instead of this

// wizard.heal.call(archer, 50, 20)

// apply looks like this

wizard.heal.apply(archer, [50, 20]);

// this has the same resultBind

Unlike call and apply, bind does not run the method it is used on, but rather returns a new function that can then be called later.

console.log(archer); // health: 30

const healArcher = wizard.heal.bind(archer, 50, 20);

healArcher();

console.log(archer); // health: 100Currying with bind

Currying is breaking down a function with multiple arguments into one or more functions that each accept a single argument.

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

let multiplyByTwo = multiply.bind(this, 2);

multiplyByTwo(4); // 8

let multiplyByTen = multiply.bind(this, 10);

multiplyByTen(6); // 60Exercise: Find the largest number in an array

const array = [1, 2, 3];

function getMaxNumber(arr) {

return Math.max.apply(null, arr);

}

getMaxNumber(array); // 3Exercise 2: How would you fix this?

const character = {

name: "Simon",

getCharacter() {

return this.name;

}

};

const giveMeTheCharacterNOW = character.getCharacter;

//How Would you fix this?

console.log("?", giveMeTheCharacterNOW()); //this should return 'Simon' but doesn't

// ANSWER

// change this line

const giveMeTheCharacterNOW = character.getCharacter.bind(character);

console.log("?", giveMeTheCharacterNOW()); // ? SimonJavaScript Types

Brittney goes into all of the types in her basic JavaScript course notes, but decided to take a deeper dive into types in JavaScript here.

| Type | Result |

|---|---|

| Undefined | undefined |

| Null | object* |

| Boolean | boolean |

| Number | number |

| BigInt (new in ECMAScript 2020) | bigint |

| String | string |

| Symbol (new in ECMAScript 2015) | symbol |

| Function object | function |

| Any other object | object |

*Null - Why does the typeof null return object? When JavaScript was first implemented, values were represented as a type tag and a value.

The objects type tag was 0 and the NULL pointer (0x00 in most platforms) consequently had 0 as a type tag as well.

A fix was proposed that would have made typeof null === 'null', but it was rejected due to legacy code that would have broken.

// Numbers

typeof 37 === "number";

typeof 3.14 === "number";

typeof 42 === "number";

typeof Math.LN2 === "number";

typeof Infinity === "number";

typeof NaN === "number"; // Despite being "Not-A-Number"

typeof Number("1") === "number"; // Number tries to parse things into numbers

typeof Number("shoe") === "number"; // including values that cannot be type coerced to a number

typeof 42n === "bigint";

// Strings

typeof "" === "string";

typeof "bla" === "string";

typeof `template literal` === "string";

typeof "1" === "string"; // note that a number within a string is still typeof string

typeof typeof 1 === "string"; // typeof always returns a string

typeof String(1) === "string"; // String converts anything into a string, safer than toString

// Booleans

typeof true === "boolean";

typeof false === "boolean";

typeof Boolean(1) === "boolean"; // Boolean() will convert values based on if they're truthy or falsy

typeof !!1 === "boolean"; // two calls of the ! (logical NOT) operator are equivalent to Boolean()

// Symbols

typeof Symbol() === "symbol";

typeof Symbol("foo") === "symbol";

typeof Symbol.iterator === "symbol";

// Undefined

typeof undefined === "undefined";

typeof declaredButUndefinedVariable === "undefined";

typeof undeclaredVariable === "undefined";

// Objects

typeof { a: 1 } === "object";

// use Array.isArray or Object.prototype.toString.call

// to differentiate regular objects from arrays

typeof [1, 2, 4] === "object";

typeof new Date() === "object";

typeof /regex/ === "object"; // See Regular expressions section for historical results

// The following are confusing, dangerous, and wasteful. Avoid them.

typeof new Boolean(true) === "object";

typeof new Number(1) === "object";

typeof new String("abc") === "object";

// Functions

typeof function() {} === "function";

typeof class C {} === "function";

typeof Math.sin === "function";Undefined vs Null: Undefined is the absence of definition, it has yet to be defined, and null is the absence of value, there is no value there.

Objects in JavaScript

Objects are one of the broadest types in JavaScript, almost "everything" is an object. MDN Standard built-in objects

- Booleans can be objects (if defined with the new keyword)

- Numbers can be objects (if defined with the new keyword)

- Strings can be objects (if defined with the new keyword)

- Dates are always objects

- Maths are always objects

- Regular expressions are always objects

- Arrays are always objects

- Functions are always objects

- Objects are always objects

Primitive vs Non Primitive

Primitive - Primitive values are defined by being immutable, they cannot be altered. The variable assigned to a primitive type may be reassigned to a new value, but the original value can not be changed in the same way objects can be modified.

Primitives are passed by value, meaning their values are copied and then placed somewhere else in the memory. They are also compared by value. There are currently 7 primitive data types in JavaScript.

- string

- number

- bigint

- boolean

- null

- undefined

- symbol

Non Primitive - The only type that leaves us with is objects.

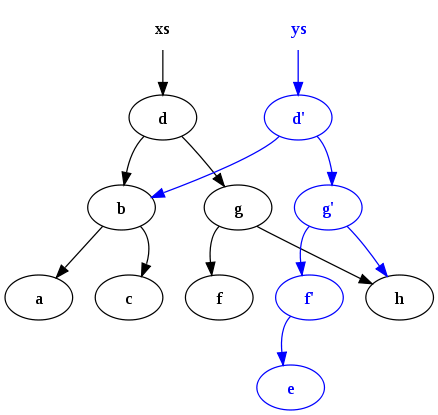

Objects are able to be mutated and their properties are passed by reference, meaning their properties are not stored separately in memory.

A new variable pointing to an object will not create a copy, but reference the original objects location in memory. Therefore, changing the 2nd object will also change the first.

// objects are passed by reference

let obj = {

name: "object 1"

};

let newObj = obj; // points to same place in memory as obj

newObj.name = "newObj"; // modifies the memory

// Since both point to the same place...

console.log(obj); // {name: newObj}

console.log(newObj); // {name: newObj}

// They are both modified.

let arr = [1, 2, 3];

let newArr = arr;

newArr.push(4);

console.log(arr); // [1, 2, 3, 4]

console.log(newArr); // [1, 2, 3, 4]There are two ways to get around this, Object.assign() or use the spread operator {...} to "spread" or expand the object into a new variable. By doing this, it will allow the new variable to be modified without changing the original. However, these only create a "shallow copy".

Shallow copy: Shallow copy is a bit-wise copy of an object. A new object is created that has an exact copy of the values in the original object.

If any of the fields of the object are references to other objects, just the reference addresses are copied i.e., only the memory address is copied.

Deep copy: A deep copy copies all fields, and makes copies of dynamically allocated memory pointed to by the fields. A deep copy occurs when an object is copied along with the objects to which it refers.

Understanding Deep and Shallow Copy

const originalObj = {

nested: {

nestedKey: "nestedValue"

},

key: "value"

};

// originalObj points to location 1 in memory

const assignObj = originalObj;

// assignObj will point to 1 in memory

const shallowObj = { ...originalObj };

// shallowObj points to a new location 2, but references location 1 for the nested object

const deepObj = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(originalObj));

// deepObj clones all parts of the object to a new memory addressconst originalObj = {

nested: {

nestedKey: "nestedValue"

},

key: "value"

};

const assignObj = originalObj;

const shallowObj = { ...originalObj };

const deepObj = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(originalObj));

console.log("originalObj: ", originalObj);

console.log("assignObj: ", assignObj);

console.log("shallowObj: ", shallowObj);

console.log("deepObj: ", deepObj);

/*

originalObj: {nested: {

nestedKey: "changed value"

},

key: "changed value"}

assignObj: {nested: {

nestedKey: "changed value"

},

key: "changed value"}

shallowObj: {nested: {

nestedKey: "changed value"

},

key: "value"}

deepObj: {nested: {

nestedKey: "nestedValue"

},

key: "value"}

*/Nifty Snippet: If you try to check if 2 objects with the same properties are equal with obj1 = obj2, it will return false.

It does this because each object has its own address in memory as we learned about. The easiest way to check the contents of the objects for equality is this.

JSON.stringify(obj1) === JSON.stringify(obj2);This will return true if all the properties are the same.

Type Coercion

Type coercion is the process of converting one type of value into another. There are 3 types of conversion in JavaScript.

- to string

- to boolean

- to number

let num = 1;

let str = "1";

num == str; // true

// notice loose equality ==, not ===

// double equals (==) will perform a type conversion

// one or both sides may undergo conversions

// in this case 1 == 1 or '1' == '1' before checking equalityStrict equals: The triple equals (===) or strict equality compares two values without type coercion. If the values are not the same type, then the values are not equal.

This is almost always the right way to check for equality in JavaScript, so you don't accidentaly coerce a value and end up with a bug in your program.

Here is the MDN Equality Comparison page and the ECMAScript Comparison Algorithm.

There are several edge cases that you will come in contact with in JavaScript as well. Check out this Comparison Table if you have questions about how types are coerced.

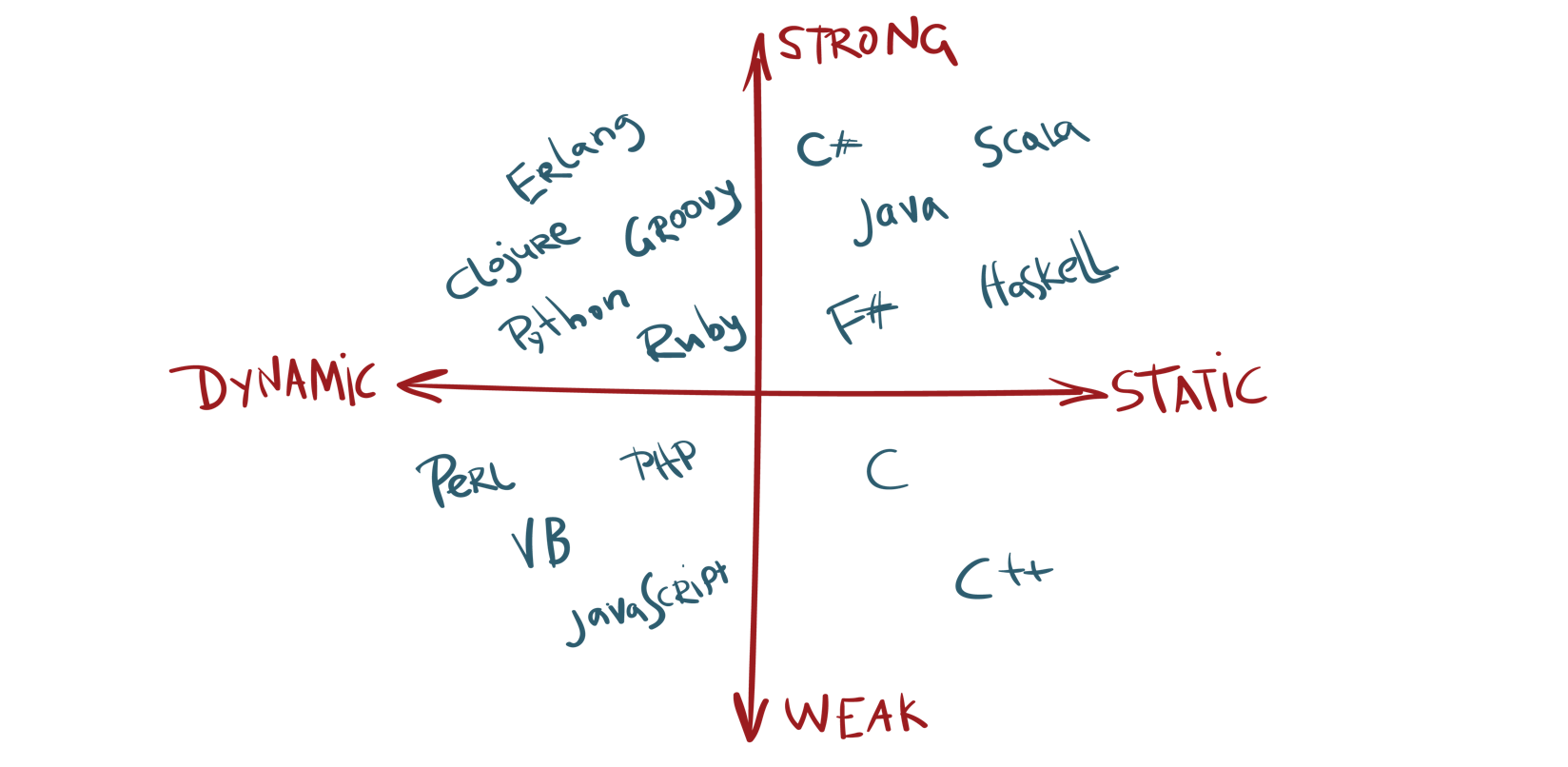

Static vs Dynamic Typed

The major difference between static and dynamic typed languages is when the types of variables are checked.

Static typed languages (Java, C, C++, C#) are checked during the compile stage, so all types are known before run-time.

Dynamic languages (JavaScript, PHP, Python, Ruby, Perl) are checked on the fly, during the execution stage.

Also, after dividing the languages into dynamic and static, they are then divided again into strong and weak typed.

Weakly typed (JavaScript, PHP, C, C++) languages can make type coercions implicitly.

Strongly typed (Python, Ruby, C#, Java) do not allow conversions between unrelated types.

The 2 Pillars: Closures and Prototypes

Closures and Prototypal Inheritance are two things that make JavaScript special and different from other programming languages.

Function Constructor

Functions are objects in JavaScript, which is not true for other languages.

Because of that, they can be called multiple ways, but they can also be constructors. A function constructor creates a new object and returns it. Every JavaScript function, is actually a function object itself.

(function() {}.contructor === Function);

// true

// function constructor

new Function("optionalArguments", "functionBody");

const four = new Function("return four"); // 4

const sum = new Function("x", "y", "return x + y");

console.log(sum(2, 3)); // 5Almost everything in JavaScript can be created with a constructor. Even basic JavaScript types like numbers and strings can be created using a constructor.

// examples of constructor functions in JavaScript

const five = new Number(5);

const assignFive = 5;

// this is different than using regular assignment

const newString = new String(`I am a new string`);

const assignString = `I am an assigned string`;

typeof five; // object

typeof assignFive; // number

typeof newString; //object

typeof assignString; // string

five === assignFive; // false

five == assignFive; // true - types are coerced

// Notice how the types are different

// depending on how they are created.

// Arrays, Booleans, Dates, Objects, and Strings

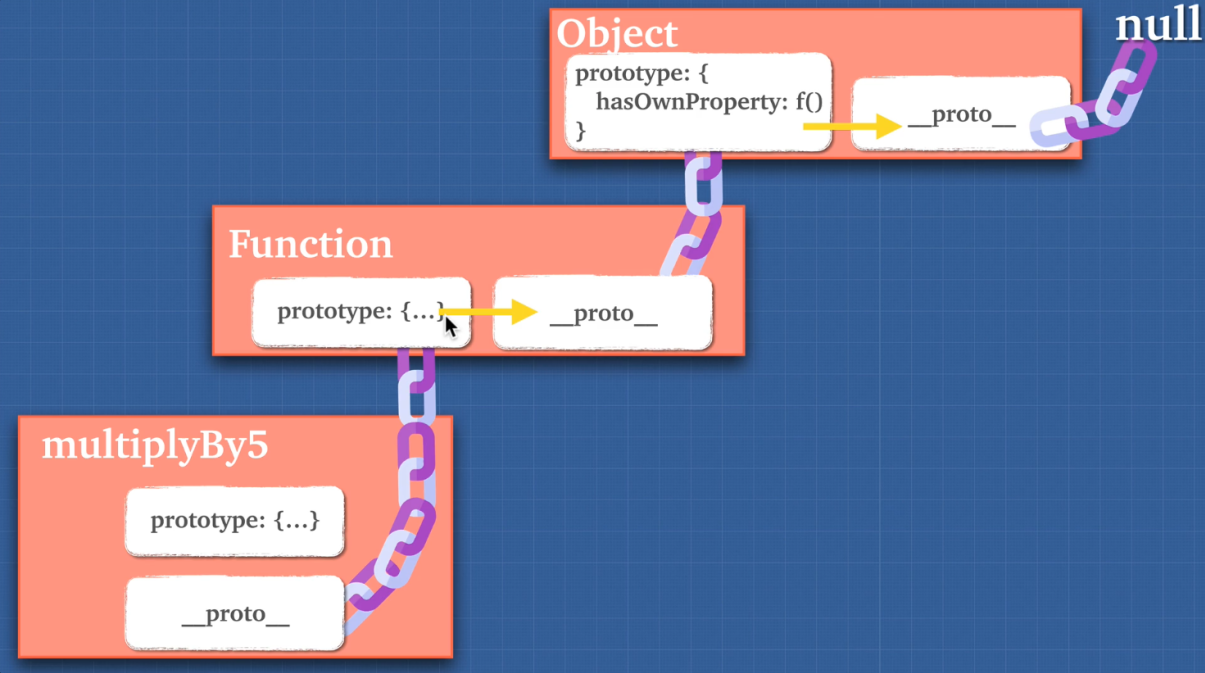

// can be created this way as well.Prototypal Inheritance

Almost all objects in Javascript pass down properties through a prototype chain. We call this chain, prototypal inheritance. The child of the object "inherits" properties from its parent.

All objects in JavaScript are descended from the Object constructor unless deliberately created or altered to not do so. The objects inherit methods and properties from Object.prototype.

The prototype property also has an accessor property called __proto__ that creates a link between the current object and points to the object it was created from, the "prototype".

Object.prototype.__proto__;

// null

Object.prototype;

{

__proto__: null;

// ...more methods and properties

}

Object;

// function Object()

// This is the object constructor function

Object.prototype.constructor;

// function Object()

// Points to the constructor

Object.__proto__;

// function () {...}

// Because it is created with a constructor functionPrototype vs \_\_proto\_\_

Understanding the difference between __proto__ and prototype can be quite a confusing concept for JavaScript developers.

Every function in JavaScript automatically gets a prototype property when it is created that gives it the call, apply, and bind methods.

It doesn't really do anything with regular functions, but in constructor functions the prototype property allows us to add our own methods to the objects we create.

The __proto__ property is what creates the link between prototype objects, the child inherits properties from the parent through the prototype chain.

Each time a new object is created in JavaScript, it uses the __proto__ getter function to use a built in constructor function based on what is being created.

This could be an Array, Boolean, Date, Number, Object, String, Function, or RegExp. Each one has their own separate properties and methods that they inherit from the constructor.

let newArr = new Array

newArr

/* []

{

// all array properties and methods

// inherited from Array constructor function.

length: 0

prototype: {

concat, forEach, pop, splice...

__proto__: Array(0)

prototype: {

__proto__: Object

prototype: {

__proto__: null

}

}

}

}Callable Object

Because functions are objects in JavaScript, this also gives them the ability to have properties added to them.

This creates a callable object, a special object that creates properties not available on normal objects.

Below is a visualization of how this works under the hood. This code can not be ran in the console, but it is a representation of how the object looks.

function say() {

console.log('say something')

}

say.yell = 'yell something'

// under the hood visual

// will not run or show in console

const funcObj = {

// name will not exist if anonymous

name: 'say',

// code to be ran

(): console.log('say something')

// properties get added

// apply, arguments, bind, call, caller, length, name, toString

yell: 'yell something',

}

// with an obj

const obj = {

// nothing gets created

}Nifty snippet: You might hear people say "Functions are first-class citizens in JavaScript".

All this means is that functions can be passed around as if they were a JavaScript type. Anything that can be done with other 7n hhb, can also be done with functions.

This introduces JavaScript to a whole different type of programming called functional programming.

Below are some examples of how functions work differently in JavaScript.

// setting functions to variables var setFuncToVar = function () {} // call function within another function a(fn) { fn() } a(function () {console.log('a new function')} // return functions within another function b() { return function c() {console.log('another func')} }

Higher Order Functions

A Higher Order Function (HOF) is a function that either takes a function as an argument or returns another function. There are 3 kinds of functions in JavaScript.

- function ()

- function (a,b)

- function hof() { return function () {} }

Instead of writing multiple functions that do the same thing, remember DRY (don't repeat yourself). Imagine in the example below, if you separated each code out into individual functions how much more code you would be writing and how much code would be repeated.

const giveAccessTo = name => `Access granted to ${name}`;

function auth(roleAmt) {

let array = [];

for (let i = 0; i < roleAmt; i++) {

array.push(i);

}

return true;

}

function checkPerson(person, fn) {

if (person.level === "admin") {

fn(100000);

} else if (person.level === "user") {

fn(500000);

}

return giveAccessTo(person.name);

}

checkPerson({ level: "admin", name: "Brittney" }, auth);

// "Access granted to Brittney"Take the example below of how you can separate code out and break it down to make it more reusable.

function multBy(a) {

return function(b) {

return a * b;

};

}

// can also be an arrow function

const multiplyBy = a => b => a * b;

const multByTwo = multiplyBy(2);

const multByTen = multiplyBy(10);

multByTwo(4); // 8

multByTen(5); // 50Closures

Closures allow a function to access variables from an enclosing scope or environment even after it leaves the scope in which it was declared.

In other words, a closure gives you access to its outer functions scope from the inner scope. The JavaScript engine will keep variables around inside functions that have a reference to them, instead of "sweeping" them away after they are popped off the call stack.

function a() {

let grandpa = 'grandpa'

return function b() {

let father = 'father'

let random = 12345 // not referenced, will get garbage collected

return function c() {

let son = 'son'

return `closure inherited all the scopes: ${grandpa} > ${father} > ${son}`

}

}

}

a()()()

// closure inherited all the scopes: grandpa > father > son

const closure = grandma => mother => daughter => return `${grandma} > ${mother} > ${daughter}`

// grandma > mother > daughterA Fun Example with Closures:

function callMeMaybe() {

const callMe = `Hey, I just met you!`

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(callMe)

}, 8640000000);

callMeMaybe()

// ONE DAY LATER

// Hey, I just met you!Do not run this in the console, it takes 1 day to timeout!

Two of the major reasons closures are so beneficial are memory efficiency and encapsulation.

Memory Efficient

Using closures makes your code more memory efficient. Take the example below.

function inefficient(idx) {

const bigArray = new Array(7000).fill("😄");

console.log("created!");

return bigArray[idx];

}

function efficient() {

const bigArray = new Array(7000).fill("😄");

console.log("created again!");

return function(idx) {

return bigArray[idx];

};

}

inefficient(688);

inefficient(1000);

inefficient(6500);

const getEfficient = efficient();

efficient(688);

efficient(1000);

efficient(6500);

// created!

// created!

// created!

// created Again!

// '😄'

// inefficient created the bigArray 3 times

// efficient created the bigArray only onceEncapsulation

Encapsulation means the restriction of direct access to some of an object's components. It hides as much as possible of an object's internal parts and only exposes the necessary parts to run. Why use encapsulation?

- Security - Controlled access

- Hide Implementation and Expose Behaviours

- Loose Coupling - Modify the implementation at any time

const encapsulation = () => {

let people = [];

const setName = name => people.push(name);

const getName = idx => people[idx];

const rmName = idx => people.splice(idx, 1);

return {

setName,

getName,

rmName

};

};

const data = encapsulation();

data.setName("Brittney"); // 0

data.getName(0); // 'Brittney'

data.rmName(0); // ['Brittney']

// you have no access to the array people

// can only change it via methods providedObject Oriented Programming vs Functional Programming

There are 2 basic philosophies when it comes to how you structure your programs, object oriented and functional. Each style has its use in programming, it is not one over the other, but merely a preference in style.

Object Oriented Programming

Object Oriented Programming, or OOP, is the idea that all code should be grouped into "boxes" (objects) to make your program easier to read and understand.

Keeping the data encapsulated helps to keep the program organized. Each object has a state that defines what it does and methods (functions on an object) that can use or modify the state.

Considering almost everything in JavaScript is an object, you would think this would be easy to do.

Say we want to create a game that has lots of characters that all have different abilities. How would we go about this?

const elf1 = {

name: 'Dobby',

type: 'house',

weapon: 'cloth',

say: function() {

return `Hi, my name is ${this.name}, I am a ${this.type} elf.`

}

attack: function() {

return `attack with ${this.weapon}`

}

}

const elf2 = {

name: 'Legolas',

type: 'high',

weapon: 'bow',

say: function() {

return `Hi, my name is ${this.name}, I am a ${this.type} elf.`

}

attack: function() {

return `attack with ${this.weapon}`

}

}

elf1.attack()

// attack with cloth

elf2.attack()

// attack with bowFactory Functions

As you can see, this code is already getting very repetitive and is not maintainable with only 1 character type.

Imagine adding more characters, things would get out of control quickly. So, another way to create objects was introduced, factory functions.

Factory functions return a new object every time they are ran. This could improve the code somewhat.

function createElf(name, type, weapon) {

return {

name: name,

type: type,

weapon: weapon,

say() {

return `Hi, my name is ${name}, I am a ${type} elf.`;

},

attack() {

return `${name} attacks with ${weapon}`;

}

};

}

const dobby = createElf("Dobby", "house", "cloth");

const legolas = createElf("Legolas", "high", "bow");

dobby.say(); // Hi, my name is Dobby, I am a house elf.

legolas.say(); // Hi, my name is Legolas, I am a high elf.

dobby.attack(); // Dobby attacks with cloth.

legolas.attack(); // Legolas attacks with bow.Stores

This is a step in the right direction, but if we added more characters, we would run into some of the same issues again.

Not only is the code not DRY, the attack method is being created and taking up memory space for every new elf. This is not very efficient.

How do we solve this? Well, we could separate the methods out into a store.

const elfMethodsStore = {

attack() {

return `attack with ${this.weapon}`;

},

say() {

return `Hi, my name is ${this.name}, I am a ${this.type} elf.`;

}

};

function createElf(name, type, weapon) {

return {

name: name, // old way

type, // with ES6 assignment, if they are the same name

weapon

};

}

// each method has to be assigned to the store method to

// create the __proto__ chain

const dobby = createElf("Dobby", "house", "cloth");

dobby.attack = elfMethodsStore.attack;

dobby.say = elfMethodsStore.say;

const legolas = createElf("Legolas", "high", "bow");

legolas.attack = elfMethodsStore.attack;

legolas.say = elfMethodsStore.say;Object.create

Having a store saved us some efficiency in memory, but this was a lot of manual work to assign each method. So, we were given Object.create to help create this chain without having to assign each method.

const elfMethodsStore = {

attack() {

return `attack with ${this.weapon}`;

},

say() {

return `Hi, my name is ${this.name}, I am a ${this.type} elf.`;

}

};

function createElf(name, type, weapon) {

// this creates the __proto__ chain to the store

let newElf = Object.create(elfMethodsStore);

console.log(newElf.__proto__); // { attack: [Function], say: [Function] }

// this assigns all the methods

newElf.name = name;

newElf.type = type;

newElf.weapon = weapon;

// this returns the new Elf with everything attached

return newElf;

}

const dobby = createElf("Dobby", "house", "cloth");

const legolas = createElf("Legolas", "high", "bow");

dobby.attack; // attack with cloth

legolas.attack; // attack with bowConstructor Functions

Using Object.create is true prototypal inheritance, the code is cleaner and easier to read. However, you will not see this being used in most programs.

Before Object.create came around, we had the ability to use constructor functions.

Constructor functions are exactly like the function constructor we talked about above. The number and string functions were constructed and invoked with the new keyword and they were capitalized.

The new keyword actually changes the meaning of this for the constructor function. Without new, this will point to the window object instead of the object that we just created.

It is best practice to capitalize constructor functions to help us identify them and know to use the new keyword. Properties added to a constructor function can only be done using the this keyword, regular variables do not get added to the object.

// constructor functions are typically capitalized

function Elf(name, type, weapon) {

// not returning anything

// "constructing" a new elf

this.name = name;

this.type = type;

this.weapon = weapon;

}

// to use a constructor function

// the "new" keyword must be used

const dobby = new Elf("Dobby", "house", "cloth");

const legolas = new Elf("Legolas", "high", "bow");

// To add methods we need to add

Elf.prototype.attack = function() {

// cannot be an arrow function

// this would be scoped to the window obj

return `attack with ${this.weapon}`;

};

// This would need to be repeated for each method.

dobby.attack(); // attack with cloth

legolas.attack(); // attack with bowNifty Snippet: A constructor function in JavaScript is actually just a constructor itself.

// What happens under the hood... const Elf = new Function( 'name', 'type', 'weapon', // the \ n just creates a new line // it can be ignored here 'this.name = name \n this.type = type \n this.weapon = weapon` ) const dobby = new Elf('Dobby', 'house', 'cloth') // This will work the same as our code above.

Class

Confused yet? Prototype is a little weird and hard to read unless you really understand your prototypal inheritance.

No one really liked using the prototype way of adding methods, so ES6 JavaScript gave us the class keyword.

However, classes in JavaScript are not true classes, they are syntactic sugar. Under the hood, it is still using the old prototype method. They are in fact just "special functions" with one big difference; functions are hoisted and classes are not. You need to declare your class before it can be used in your codebase.

Classes also come with a new method, the constructor that creates and instantiates an object created with class. Classes are able to be extended upon using the extends keyword, allowing subclasses to be created.

If there is a constructor present in the extended class, the super keyword is needed to link the constructor to the base class. You can check if something is inherited from a class by using the keyword instanceof to compare the new object to the class.

class Character {

constructor(name, weapon) {

this.name = name;

this.weapon = weapon;

}

attack() {

return `attack with ${this.weapon}`;

}

}

class Elf extends Character {

constructor(name, weapon, type) {

super(name, weapon);

// pulls in name and weapon from Character

this.type = type;

}

}

class Ogre extends Character {

constructor(name, weapon, color) {

super(name, weapon);

this.color = color;

}

enrage() {

return `double attack power`;

}

}

const legolas = new Elf("Legolas", "high", "bow");

const gruul = new Ogre("Gruul", "club", "gray");

legolas.attack(); // attack with bow

gruul.enrage(); // double attack power

gruul.attack(); // attack with club

legolas instanceof Elf; //true

gruul instanceof Ogre; //truePrivate and public fields

Most class based languages have the ability to create either public or private fields within a class. Adding these to classes in JavaScript is still an experimental feature in development.

Support in browsers is limited, but can be implemented with systems like Babel.

Public declarations are set above the constructor and can be used within the class, but do not get added to a new instance.

The private declarations are set with the # sign in front of the variable and are only accessible within that class, they cannot be accessed or changed from outside.

// public declarations

class Rectangle {

height = 0;

width;

constructor(height, width) {

this.height = height;

this.width = width;

}

}

// private declarations

class Rectangle {

#height = 0;

#width;

constructor(height, width) {

this.#height = height;

this.#width = width;

}

}So, did we obtain perfect object oriented programming?

Well, that is up for debate. It is really up to you the developer to decide which style of writing you like best. We did learn that object oriented programming helps make you code more understandable, easy to extend, easy to maintain, memory efficient, and DRY!

Nifty Snippet: Why didn't Eich just add classes to JavaScript in the beginning?

"If I had done classes in JavaScript back in May 1995, I would have been told that it was too much like Java or the JavaScript was competing with Java... I was under marketing orders to make it look like Java but not make it too big for its britches... [it] needed to be a silly little brother language." - Brendan Eich

Functional Programming

Functional programming has the same goals in mind as object oriented programming, to keep your code understanable, easy to extend, easy to maintain, memory efficient, and DRY.

Instead of objects, it uses reusable functions to create and act on data.

Functional programming is based on a separation of concerns similar to object oriented programming. However, in functional programming, there is a complete separation between the data and the behaviors of a program.

There is also an idea that once something is created, it should not be changed, being immutable.

Unlike OOP, shared state is avoided as functional programming works on the idea of pure functions.

Pure Functions

A pure function has no side effects to anything outside of it and given the same input will always output the same value. They do not change any data passed into them, but create new data to return without altering the original.

However, it is not possible to have 100% pure functions. At some point you need to interact with the dom or fetch an api.

Even console.log makes a function unpure because it uses the window object outside of the function. The fact is a program cannot exist without side effects.

So, the goal of functional programming is to minimize side effects by isolating them away from the data. Build lots of very small, reusable and predictable pure functions that do the following:

- Complete 1 task per function.

- Do not mutate state.

- Do not share state.

- Be predictable.

- Be composable, one input and one output.

- Be pure if possible.

- Return something.

Referential transparency

One important concept of functional programming is referential transparency, the ability to replace an expression with the resulting value without changing the result of the program.

function a(num1, num2) {

return num1 + num2;

}

function b(num) {

return num * 2;

}

b(a(3, 4)); // 14

// a should always return 7

// so it could be changed to

b(7); // 14

// and the output is the sameIdempotence

Idempotence is another important piece of functional programming. It is the idea that given the same input to a function, you will always return the same output. The function could be used over and over again and nothing changes.This is how you make your code predictable.

Imperative vs Declarative

__Imperative programming__ tells the computer what to do and how to complete it.Declarative programming only tells the computer what to do, but not how to do things.

Humans are declarative by nature, but computers typically need more imperative type programming.

However, using higher level languages like JavaScript is actually being less declarative. This is important in function programming because we want to be more declarative to better understand our code and let the computer handle the dirty work of figuring out the best way to do something.

// more imperative

for (let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

console.log(i);

}

// more declarative

let arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10];

arr.forEach(item => console.log(item));Immutability

Immutability is simply not modifying the original data or state. Instead we should create copies of the state inside our functions and return a new version of the state.

// Bad code

const obj = {name: 'Brittney'}

function clone(obj) {

return {...obj} // this is pure

}

obj.name = 'Joe' //mutated the state

// Better code

function updateName(obj) {

const newObj = clone(obj)

newObj.name = 'Joe'

return newObj

}

const updatedNameObj = updateName(obj)

console.log(`obj = ${obj}`, `updatedNameObj = ${updatedNameObj})

// obj = {name: 'Brittney'} updatedNameObj = {name: 'Joe'}You may be thinking that this could get really expensive, memory wise, to just copy code over and over. However, there is something called structural sharing that allows the data to only copy new information and points to the original state for any commonalities.

Partial Application

Partial application is expanding on the idea of currying and taking it a step farther by separating a parameter out. If you have more than 2 arguments in a functions, then you can bind one of them to a value to be used later.

const multiply = (a, b, c) => a * b * c;

const curriedMultiplyBy5 = multiply.bind(null, 5); // this is null

curriedMultiplyBy5(4, 10); // 200Pipe and Compose

In JavaScript it is best for speed and efficiency to keep functions small and reusable.

Function composition is the idea that you lay out your functions like a factory assembly line. The actual functions pipe() and compose() don't actually exist in JavaScript yet, but there are many libraries that use them.

You can however create your own versions of them. The compose() function reads the functions from right to left and the pipe() function will read from left to right.

// create our own COMPOSE function

const compose = (fn1, fn2) => data => fn1(fn2(data));

// create our own PIPE function

const pipe = (fn1, fn2) => data => fn2(fn1(data));

const multiplyBy3 = num => num * 3;

const makePositive = num => Math.abs(num);

// use compose to combine multiple functions

const composeFn = compose(multiplyBy3, makePositive);

const pipeFn = pipe(multiplyBy3, makePositive);

composeFn(-50); // 150

pipeFn(-50); // 150

// essentially we are doing this

// fn1(fn2(fn3(50)))

// compose(fn1, fn2, fn3)(50)

// pipe(fn3, fn2, fn1)(50)Nifty Snippet: The Pipeline Operator is in the experimental stage 1 of being introduced to JavaScript.

Stage 1 means that it has only started the process and could be years before it is a part of the language. The pipeline operator, |>, would be syntactic sugar for composing and piping functions the long way.

This would improve readability when chaining multiple functions.

const double = n => n * 2; const increment = n => n + 1; // without pipeline operator double(increment(double(double(5)))); // 42 // with pipeline operator 5 |> double |> double |> increment |> double; // 42

Arity

Arity simply means the number of arguments a function takes. The more parameters a function has the harder it becomes to break apart and reuse. Try to stick to only 1 or 2 parameters when writing functions.

Reviewing Functional Programming

So, is functional programming the answer to everything?

No, but it is great in situations where you have to perform different operations on the same set of data.

Functional programming just lays the foundation for creating reusable functions that can be moved around as needed.

For example, it is great in areas of industry and machine learning and it is even in some front end libraries like React and Redux. Redux really popularized functional programming for JavaScript developers.

I'll leave you with one more example, a basic shopping cart.

const user = {

name: "Kim",

active: true,

cart: [],

purchases: []

};

const userHistory = [];

function addToCart(user, item) {

userHistory.push(

Object.assign({}, user, { cart: user.cart, purchases: user.purchases })

);

const updateCart = user.cart.concat(item);

return Object.assign({}, user, { cart: updateCart });

}

function taxItems(user) {

userHistory.push(

Object.assign({}, user, { cart: user.cart, purchases: user.purchases })

);

const { cart } = user;

const taxRate = 1.4;

const updatedCart = cart.map(item => {

return {

name: item.name,

price: item.price * taxRate

};

});

return Object.assign({}, user, { cart: updatedCart });

}

function buyItems(user) {

userHistory.push(

Object.assign({}, user, { cart: user.cart, purchases: user.purchases })

);

return Object.assign({}, user, { purchases: user.cart });

}

function emptyCart(user) {

userHistory.push(

Object.assign({}, user, { cart: user.cart, purchases: user.purchases })

);

return Object.assign({}, user, { cart: [] });

}

function refundItem(user, item) {

userHistory.push(

Object.assign({}, user, { cart: user.cart, purchases: user.purchases })

);

const { purchases } = user;

const refundItem = purchases.splice(item);

return Object.assign({}, user, { purchases: refundItem });

}

const compose = (fn1, fn2) => (...args) => fn1(fn2(...args));

const purchaseItems = (...fns) => fns.reduce(compose);

purchaseItems(

emptyCart,

buyItems,

taxItems,

addToCart

)(user, { name: "laptop", price: 200 });

refundItem(user, { name: "laptop", price: 200 });

console.log(userHistory);Composition vs Inheritance

Composition is what we just did with FP, creating small reusable functions to make code modular.

Inheritance is what we did with OOP, creating a class and extending it to subclasses that inherit the properties.

In OOP we create few operations on common data that is stateful with side effects.

In FP we create many operations on fixed data with pure functions that don't mutate state. There is a big debate over which one is better and most people believe that composition is better.

OOP Problems